Read the Passage 1alfred I Ruled England

| Edward the Elderberry | |

|---|---|

Portrait miniature from a 13th-century genealogical curlicue depicting Edward | |

| King of the Anglo-Saxons | |

| Reign | 26 October 899– 17 July 924 |

| Coronation | 8 June 900 Kingston upon Thames |

| Predecessor | Alfred the Great |

| Successor | Æthelstan (or Ælfweard, disputed) |

| Born | c. 874 |

| Died | 17 July 924 Farndon, Cheshire, Mercia |

| Burying | New Minster, Winchester, later on translated to Hyde Abbey |

| Spouses |

|

| Result more ... |

|

| Business firm | Wessex |

| Begetter | Alfred the Bang-up |

| Mother | Ealhswith |

Edward the Elder [a] (c. 874 – 17 July 924) was Male monarch of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elderberry son of Alfred the Swell and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a claiming from his cousin Æthelwold, who had a strong claim to the throne as the son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor, Æthelred.

Alfred had succeeded Æthelred as king of Wessex in 871, and almost faced defeat against the Danish Vikings until his decisive victory at the Battle of Edington in 878. After the battle, the Vikings yet ruled Northumbria, Due east Anglia and eastern Mercia, leaving only Wessex and western Mercia under Anglo-Saxon command. In the early 880s Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, the ruler of western Mercia, accustomed Alfred'due south lordship and married his daughter Æthelflæd, and around 886 Alfred adopted the new title Male monarch of the Anglo-Saxons every bit the ruler of all Anglo-Saxons not subject area to Danish dominion. Edward inherited the new championship when Alfred died in 899.

In 910 a Mercian and Westward Saxon army inflicted a decisive defeat on an invading Northumbrian army, ending the threat from the northern Vikings. In the 910s, Edward conquered Viking-ruled southern England in partnership with his sister Æthelflæd, who had succeeded as Lady of the Mercians post-obit the expiry of her husband in 911. Historians dispute how far Mercia was dominated by Wessex during this menses, and subsequently Æthelflæd's expiry in June 918, her daughter Ælfwynn briefly became second Lady of the Mercians, but in December Edward took her into Wessex and imposed straight dominion on Mercia. Past the finish of the 910s he ruled Wessex, Mercia and East Anglia, and only Northumbria remained under Viking rule. In 924 he faced a Mercian and Welsh revolt at Chester, and after putting it down he died at Farndon in Cheshire on 17 July 924. He was succeeded past his eldest son, Æthelstan. Edward's 2 youngest sons later reigned equally Kings Edmund I and Eadred.

Edward was admired by medieval chroniclers, and in the view of William of Malmesbury, he was "much junior to his begetter in the cultivation of messages" merely "incomparably more glorious in the ability of his rule". He was largely ignored by modern historians until the 1990s, and Nick Higham described him as "maybe the most neglected of English language kings", partly because few chief sources for his reign survive. His reputation rose in the late twentieth century and he is now seen every bit destroying the power of the Vikings in southern England while laying the foundations for a south-centred united English kingdom.

Background [edit]

Mercia was the dominant kingdom in southern England in the eighth century and maintained its position until it suffered a decisive defeat past Wessex at the Battle of Ellandun in 825. Thereafter the two kingdoms became allies, which was to be an important cistron in English resistance to the Vikings.[one] In 865 the Danish Viking Slap-up Infidel Army landed in East Anglia and used this as a starting signal for an invasion. The East Anglians were forced to pay off the Vikings, who invaded Northumbria the following year. They appointed a puppet king in 867, and then moved on Mercia, where they spent the wintertime of 867–868. Rex Burgred of Mercia was joined past Rex Æthelred of Wessex and his brother, the future King Alfred, for a combined attack on the Vikings, who refused an engagement; in the stop the Mercians bought peace with them. The post-obit year, the Danes conquered Due east Anglia, and in 874 they expelled King Burgred and, with their support, Ceolwulf became the terminal King of Mercia. In 877 the Vikings partitioned Mercia, taking the eastern regions for themselves and allowing Ceolwulf to keep the western ones. In early on 878 they invaded Wessex, and many West Saxons submitted to them. Alfred, who was now king, was reduced to a remote base in the Isle of Athelney in Somerset, but the state of affairs was transformed when he won a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington. He was thus able to prevent the Vikings from taking Wessex and western Mercia, although they even so occupied Northumbria, Due east Anglia and eastern Mercia.[2]

Childhood [edit]

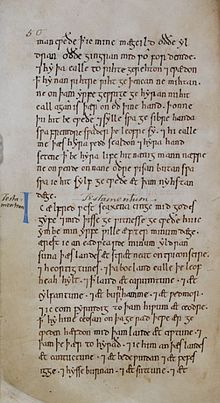

A page from the volition of Alfred the Keen, headed Testamentum in a afterward hand, which left the bulk of his estate to Edward

Edward's parents, Alfred and Ealhswith, married in 868. Ealhswith's begetter was Æthelred Mucel, Ealdorman of the Gaini, and her female parent, Eadburh, was a fellow member of the Mercian purple family. Alfred and Ealhswith had five children who survived childhood. The oldest was Æthelflæd, who married Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, and ruled as Lady of the Mercians after his death. Edward was side by side, and the second daughter, Æthelgifu, became abbess of Shaftesbury. The third girl, Ælfthryth, married Baldwin, Count of Flanders, and the younger son, Æthelweard, was given a scholarly education, including learning Latin. This would usually suggest that he was intended for the church, but information technology is unlikely in Æthelweard's case as he later had sons. There were as well an unknown number of children who died young. Neither part of Edward's name, which means 'protector of wealth', had been used previously by the Due west Saxon royal house, and Barbara Yorke suggests that he may accept been named after his maternal grandmother Eadburh, reflecting the West Saxon policy of strengthening links with Mercia.[3]

Historians estimate that Edward was probably born in the mid-870s. His eldest sister, Æthelflæd, was probably born near a year afterward her parents' union, and Edward was brought up with his youngest sis, Ælfthryth; Yorke argues that he was therefore probably nearer in age to Ælfthryth than Æthelflæd. Edward led troops in battle in 893, and must take been of marriageable historic period in that year as his oldest son Æthelstan was born about 894.[iv] Co-ordinate to Asser in his Life of King Alfred, Edward and Ælfthryth were educated at court past male person and female tutors, and read ecclesiastical and secular works in English, such as the Psalms and Erstwhile English poems. They were taught the courtly qualities of gentleness and humility, and Asser wrote that they were obedient to their father and friendly to visitors. This is the only known example of an Anglo-Saxon prince and princess receiving the aforementioned upbringing.[v]

Ætheling [edit]

Every bit a son of a king, Edward was an ætheling, a prince of the imperial house who was eligible for kingship. Even though he had the advantage of being the eldest son of the reigning king, his accession was not assured as he had cousins who had a stiff merits to the throne. Æthelhelm and Æthelwold were sons of Æthelred, Alfred'southward older brother and predecessor equally rex, only they had been passed over because they were infants when their male parent died. Asser gives more information about Edward's childhood and youth than is known about other Anglo-Saxon princes, providing details near the training of a prince in a period of Carolingian influence, and Yorke suggests that we may know so much due to Alfred's efforts to portray his son as the near throneworthy ætheling.[half-dozen]

Æthelhelm is only recorded in Alfred's will of the mid-880s, and probably died at some fourth dimension in the next decade, but Æthelwold is listed in a higher place Edward in the only charter where he appears, probably indicating a college status. Æthelwold may too have had an advantage because his mother Wulfthryth witnessed a charter as queen, whereas Edward's female parent Ealhswith never had a higher status than male monarch'south wife.[seven] Still, Alfred was in a position to give his own son considerable advantages. In his will, he left only a handful of estates to his blood brother's sons, and the bulk of his belongings to Edward, including all his booklands (country vested in a lease which could be alienated by the holder, equally opposed to folkland, which had to pass to heirs of the body) in Kent.[8] Alfred also advanced men who could be depended on to back up his plans for his succession, such as his brother-in-law, a Mercian ealdorman called Æthelwulf, and his son-in-constabulary Æthelred. Edward witnessed several of his begetter'due south charters, and ofttimes accompanied him on royal peregrinations.[ix] In a Kentish lease of 898 Edward witnessed as rex Saxonum, suggesting that Alfred may have followed the strategy adopted past his grandfather Egbert of strengthening his son's claim to succeed to the West Saxon throne past making him sub-king of Kent.[10]

One time Edward grew up, Alfred was able to give him military commands and experience in royal administration.[11] The English defeated renewed Viking attacks in 893 to 896, and in Richard Abels' view, the glory belonged to Æthelred and Edward rather than Alfred himself. In 893 Edward defeated the Vikings in the Battle of Farnham, although he was unable to follow up his victory as his troops' period of service had expired and he had to release them. The situation was saved by the arrival of troops from London led by Æthelred.[12] Yorke argues that although Alfred packed the witan with members whose interests lay in the continuation of Alfred's line, that may non have been sufficient to ensure Edward'south accession if he had non displayed his fitness for kingship.[13]

In about 893, Edward probably married Ecgwynn, who bore him two children, the hereafter King Æthelstan and a daughter who married Sitric Cáech, a Viking King of York. The twelfth-century chronicler William of Malmesbury described Ecgwynn as an illustris femina (noble lady), and stated that Edward chose Æthelstan as his heir equally king. She may have been related to St Dunstan, the aristocratic 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury. Only William of Malmesbury also stated that Æthelstan'south accession in 924 was opposed by a nobleman who claimed that his mother was a concubine of low nascence.[14] The suggestion that Ecgwynn was Edward'southward mistress is accustomed by some historians such as Simon Keynes and Richard Abels,[xv] simply Yorke and Æthelstan's biographer, Sarah Foot, disagree, arguing that the allegations should be seen in the context of the disputed succession in 924, and were not an consequence in the 890s.[16] Ecgwynn probably died by 899, as around the time of Alfred'southward death Edward married Ælfflæd, the daughter of Ealdorman Æthelhelm, probably of Wiltshire.[17]

Janet Nelson suggests that there was conflict between Alfred and Edward in the 890s. She points out that the contemporary Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, produced under courtroom auspices in the 890s, does not mention Edward's military successes. These are known only from the tardily tenth century relate of Æthelweard, such as his account of the Battle of Farnham, in which in Nelson'southward view "Edward's military prowess, and popularity with a following of young warriors, are highlighted". Towards the terminate of his life Alfred invested his immature grandson Æthelstan in a ceremony which historians come across as designation as eventual successor to the kingship. Nelson argues that while this may have been proposed by Edward to back up the accession of his ain son, on the other hand it may take been intended by Alfred as role of a scheme to dissever the kingdom between his son and grandson. Æthelstan was sent to be brought upwards in Mercia past Æthelflæd and Æthelred, just it is not known whether this was Alfred'southward idea or Edward'southward. Alfred's wife Ealhswith was ignored in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in her husband'southward lifetime, but emerged from obscurity when her son acceded. This may exist considering she supported her son against her husband.[18]

Æthelwold'south defection [edit]

Alfred died on 26 October 899 and Edward succeeded to the throne, but Æthelwold disputed the succession.[19] He seized the majestic estates of Wimborne, symbolically of import as the place where his male parent was buried, and Christchurch, both in Dorset. Edward marched with his army to the nearby Atomic number 26 Age hillfort at Badbury Rings. Æthelwold declared that he would live or die at Wimborne, but then left in the dark and rode to Northumbria, where the Danes accepted him as king.[20] Edward was crowned on 8June 900 at Kingston upon Thames.[b]

In 901, Æthelwold came with a fleet to Essex, and the following yr he persuaded the E Anglian Danes to invade English Mercia and northern Wessex, where his ground forces looted and then returned habitation. Edward retaliated by ravaging East Anglia, but when he retreated the men of Kent disobeyed the order to retire, and were intercepted by the Danish army. The two sides met at the Battle of the Holme (perhaps Holme in Huntingdonshire) on thirteen December 902. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Danes "kept the place of slaughter", meaning that they won the battle, but they suffered heavy losses, including Æthelwold and a King Eohric, possibly of the Eastward Anglian Danes. Kentish losses included Sigehelm, ealdorman of Kent and father of Edward's 3rd wife, Eadgifu. Æthelwold'south death ended the threat to Edward'south throne.[22]

King of the Anglo-Saxons [edit]

Silvery pseudo-money brooch found at the Villa Wolkonsky in Rome. It is based on a coin of Edward the Elder and is probably contemporary.[23]

In London in 886 Alfred had received the formal submission of "all the English people that were non under subjection to the Danes", and thereafter he adopted the title Anglorum Saxonum king (King of the Anglo-Saxons), which is used in his later charters and all but ii of Edward'due south. This is seen by Keynes as "the invention of a wholly new and distinctive polity", covering both West Saxons and Mercians, which was inherited by Edward with the support of Mercians at the West Saxon court, of whom the most important was Plegmund, Archbishop of Canterbury. In 903 Edward issued several charters apropos state in Mercia. Three of them are witnessed by the Mercian leaders and their daughter Ælfwynn, and they all incorporate a statement that Æthelred and Æthelflæd "then held rulership and ability over the race of the Mercians, under the aforesaid king". Other charters were issued by the Mercian leaders which did not contain whatever acquittance of Edward'south authorisation, but they did not upshot their own coinage.[24] This view of Edward's status is accustomed by Martin Ryan, who states that Æthelred and Æthelflæd had "a considerable but ultimately subordinate share of purple authorization" in English Mercia.[25]

Other historians disagree. Pauline Stafford describes Æthelflæd equally "the last Mercian queen",[26] while in Charles Insley's view Mercia kept its independence until Æthelflæd'southward death in 918.[27] Michael Davidson contrasts the 903 charters with one of 901 in which the Mercian rulers were "by grace of God, property, governing and defending the monarchy of the Mercians". Davidson comments that "the evidence for Mercian subordination is decidedly mixed. Ultimately, the credo of the 'Kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons' may have been less successful in achieving the assimilation of Mercia and more than something which I would see as a murky political coup." The Anglo-Saxon Relate was compiled at the West Saxon court from the 890s, and the entries for the late ninth and early tenth centuries are seen by historians as reflecting the West Saxon viewpoint; Davidson observes that "Alfred and Edward possessed skilled 'spin doctors'".[28] Some versions of the Relate incorporate part of a lost Mercian Annals, which gives a Mercian perspective and details of Æthelflæd's campaign against the Vikings.[25]

In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, connectedness by marriage with the Westward Saxon royal house was seen every bit prestigious by continental rulers. In the mid-890s Alfred had married his daughter Ælfthryth to Baldwin Ii of Flemish region, and in 919 Edward married his daughter Eadgifu to Charles the Unproblematic, Male monarch of West Francia. In 925, afterward Edward's death, another daughter Eadgyth married Otto, the futurity King of Frg and (after Eadgyth'south death) Holy Roman Emperor.[29]

Conquest of the southern Danelaw [edit]

No battles are recorded betwixt the Anglo-Saxons and the Danish Vikings for several years afterward the Boxing of the Holme, just in 906 Edward agreed peace with the E Anglian and Northumbrian Danes, suggesting that there had been conflict. According to one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle he fabricated peace "of necessity", which implies that he was forced to buy them off.[nineteen] He encouraged Englishmen to purchase land in Danish territory, and two charters survive relating to estates in Bedfordshire and Derbyshire.[30] In 909 Edward sent a combined West Saxon and Mercian army which harassed the Northumbrian Danes, and seized the bones of the Northumbrian royal saint Oswald from Bardney Abbey in Lincolnshire. Oswald was translated to a new Mercian minster established by Æthelred and Æthelflæd in Gloucester and the Danes were compelled to have peace on Edward's terms.[31] In the following year, the Northumbrian Danes retaliated by raiding Mercia, simply on their style dwelling they were met past a combined Mercian and West Saxon army at the Boxing of Tettenhall, where the Vikings suffered a disastrous defeat. Subsequently that, the Northumbrian Danes never ventured s of the River Humber, and Edward and his Mercian allies were able to concentrate on conquering the southern Danelaw in East Anglia and the V Boroughs of Viking east Mercia: Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford.[19]

In 911 Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, died, and Edward took control of the Mercian lands around London and Oxford. Æthelred was succeeded as ruler by his widow Æthelflæd (Edward'south sister) equally Lady of the Mercians, and she had probably been acting as ruler for several years every bit Æthelred seems to have been incapacitated in later life.[32]

Edward and Æthelflæd so began the structure of fortresses to guard confronting Viking attacks and protect territory captured from them. In November 911, he constructed a fort on the northward banking concern of the River Lea at Hertford to guard confronting set on by the Danes of Bedford and Cambridge. In 912, he marched with his army to Maldon in Essex, and ordered the building of a fort at Witham and a second fort at Hertford, which protected London from attack and encouraged many English living under Danish rule in Essex to submit to him. In 913 there was a pause in his activities, although Æthelflæd continued her fortress edifice in Mercia.[33] In 914 a Viking army sailed from Brittany and ravaged the Severn estuary. It then attacked Ergyng in due south-due east Wales (now Archenfield in Herefordshire) and captured Bishop Cyfeilliog. Edward ransomed him for the large sum of forty pounds of argent. The Vikings were defeated by the armies of Hereford and Gloucester, and gave hostages and oaths to proceed the peace. Edward kept an army on the south side of the estuary in case the Vikings broke their promises, and he twice had to repel attacks. In the fall the Vikings moved on to Republic of ireland. The episode suggests that south-due east Wales fell within the West Saxon sphere of ability, different Brycheiniog just to the n, where Mercia was dominant.[34] In late 914 Edward built ii forts at Buckingham, and Earl Thurketil, the leader of the Danish regular army at Bedford submitted to him. The following year he occupied Bedford, and constructed some other fortification on the south bank of the River Neat Ouse against a Viking one on the due north bank. In 916 Edward returned to Essex and built a fort at Maldon to eternalize the defence of Witham. He also helped Earl Thurketil and his followers to leave England, reducing the number of Viking armies in the Midlands.[35]

The decisive yr in the state of war was 917. In April Edward congenital a fort at Towcester equally a defence force against the Danes of Northampton, and another at an unidentified place called Wigingamere. The Danes launched unsuccessful attacks on Towcester, Bedford and Wigingamere, while Æthelflæd captured Derby, showing the value of the English defensive measures, which were aided by disunity and a lack of coordination among the Viking armies. The Danes had congenital their own fortress at Tempsford in Bedfordshire, but at the stop of the summer the English stormed information technology and killed the last Danish king of E Anglia. The English so took Colchester, although they did not attempt to hold it. The Danes retaliated by sending a large army to lay siege to Maldon, but the garrison held out until it was relieved and the retreating army was heavily defeated. Edward then returned to Towcester and reinforced its fort with a stone wall, and the Danes of nearby Northampton submitted to him. The armies of Cambridge and East Anglia also submitted, and past the end of the year the only Danish armies still holding out were those of 4 of the Five Boroughs, Leicester, Stamford, Nottingham, and Lincoln.[36]

In early on 918, Æthelflæd secured the submission of Leicester without a fight, and the Danes of Northumbrian York offered her their allegiance, probably for protection against Norse (Norwegian) Vikings who had invaded Northumbria from Ireland, but she died on 12 June earlier she could take up the proposal. The same offering is not known to have been made to Edward, and the Norse Vikings took York in 919. Co-ordinate to the main Westward Saxon version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, afterward Æthelflæd'southward death the Mercians submitted to Edward, but the Mercian version (the Mercian Register) states that in December 918 her daughter Ælfwynn "was deprived of all authority in Mercia and taken into Wessex". Mercia may have made a bid for continued semi-independence which was suppressed past Edward, and it and then came under his direct dominion. Stamford had surrendered to Edward before Æthelflæd's death, and Nottingham did the aforementioned shortly after. Co-ordinate to the Anglo-Saxon Relate for 918, "all the people who had settled in Mercia, both Danish and English, submitted to him". This would mean that he ruled all England south of the Humber, only information technology is non clear whether Lincoln was an exception, as coins of Viking York in the early 920s were probably minted at Lincoln.[37] Some Danish jarls were allowed to proceed their estates, although Edward probably as well rewarded his supporters with land, and some he kept in his own hands. Coin evidence suggests that his authority was stronger in the Eastward Midlands than in E Anglia.[38] Iii Welsh kings, Hywel Dda, Clydog and Idwal Foel, who had previously been subject to Æthelflæd, now gave their allegiance to Edward.[39]

Silvery penny of Edward the Elder

Coinage [edit]

The master currency in subsequently Anglo-Saxon England was the silver penny, and some coins carried a stylised portrait of the king. Edward's coins had "EADVVEARD Rex" on the obverse and the name of the moneyer on the reverse. The places of issue were non shown in his reign, but they were in that of his son Æthelstan, allowing the location of many moneyers of Edward'south reign to be established. There were mints in Bath, Canterbury, Chester, Chichester, Derby, Exeter, Hereford, London, Oxford, Shaftesbury, Shrewsbury, Southampton, Stafford, Wallingford, Wareham, Winchester and probably other towns. No coins were struck in the name of Æthelred or Æthelflæd, but from around 910 mints in English Mercia produced coins with an unusual decorative design on the opposite. This ceased before 920, and probably represents Æthelflæd's manner of distinguishing her coinage from that of her brother. In that location was besides a minor issue of coins in the name of Plegmund, Archbishop of Canterbury. There was a dramatic increase in the number of moneyers over Edward's reign, fewer than 25 in the south in the kickoff ten years rising to 67 in the last ten years, around five in English language Mercia rising to 23, plus 27 in the conquered Danelaw.[40]

Church [edit]

In 908, Plegmund conveyed the alms of the English king and people to the Pope, the first visit to Rome past an Archbishop of Canterbury for about a century, and the journey may take been to seek papal approval for a proposed re-organisation of the Westward Saxon sees.[41] When Edward came to the throne Wessex had two dioceses, Winchester, held by Denewulf, and Sherborne, held by Asser.[42] In 908 Denewulf died and was replaced the post-obit twelvemonth past Frithestan; soon later Winchester was divided into two sees, with the cosmos of the diocese of Ramsbury roofing Wiltshire and Berkshire, while Winchester was left with Hampshire and Surrey. Forged charters date the partition to 909, only this may not be correct. Asser died in the aforementioned year, and at some date between 909 and 918 Sherborne was divided into three sees, Crediton roofing Devon and Cornwall, and Wells covering Somerset, leaving Sherborne with Dorset.[43] The effect of the changes was to strengthen the status of Canterbury compared with Winchester and Sherborne, but the division may have been related to a modify in the secular functions of West Saxon bishops, to get agents of majestic government in shires rather than provinces, assisting in defence and taking office in shire courts.[44]

At the beginning of Edward's reign, his mother Ealhswith founded the abbey of St Mary for nuns, known as the Nunnaminster, in Winchester.[45] Edward's girl Eadburh became a nun at that place, and she was venerated equally a saint and the subject of a hagiography past Osbert of Clare in the twelfth century.[46] In 901, Edward started building a major religious community for men, possibly in accordance with his father's wishes. The monastery was next to Winchester Cathedral, which became known as the Onetime Minster while Edward'due south foundation was called the New Minster. It was much larger than the Old Minster, and was probably intended as a majestic mausoleum.[47] Information technology acquired relics of the Breton Saint Judoc, which probably arrived in England from Ponthieu in 901, and the body of one of Alfred's closest advisers, Grimbald, who died in the same year and who was soon venerated equally a saint. Edward's mother died in 902, and he buried her and Alfred there, moving his father's torso from the Sometime Minster. Burials in the early 920s included Edward himself, his brother Æthelweard, and his son Ælfweard. On the other manus, when Æthelstan became king in 924, he did not show any favour to his male parent'southward foundation, probably because Winchester sided against him when the throne was disputed after Edward's decease. The merely other male monarch buried at the New Minster was Eadwig, in 959.[48]

Edward'southward conclusion not to expand the One-time Minster, merely rather to overshadow information technology with a much larger building, suggests antagonism towards Bishop Denewulf, and this was compounded by forcing the Onetime Minster to cede both land for the new site, and an manor of 70 hides at Beddington to provide an income for the New Minster. Edward was remembered by the New Minster every bit a benefactor, but at the One-time Minster as male monarch avidus (greedy king).[49] He may accept built the new church because he did not call up that the Erstwhile Minster was grand plenty to be the royal mausoleum for kings of the Anglo-Saxons, not just the W Saxons similar their predecessors.[50] Alan Thacker comments:

- Edward's method of endowing New Minster was of a piece with his ecclesiastical policy in full general. Like his father he gave little to the church building — indeed, judging by the dearth of charters for much of his reign he seems to have given away little at all... More than any other, Edward's kingship seems to epitomise the new hard-nosed monarchy of Wessex, adamant to exploit all its resources, lay and ecclesiastical, for its own benefit.[51]

Patrick Wormald observes: "The idea occurs that neither Alfred nor Edward was greatly beloved at Winchester Cathedral; and one reason for Edward's moving his begetter'southward trunk into the new family shrine next door was that he was surer of sincere prayers there."[52]

Learning and culture [edit]

The standard of Anglo-Saxon learning declined severely in the ninth century, particularly in Wessex, and Mercian scholars such as Plegmund played a major function in the revival of learning initiated by Alfred. Mercians were prominent at the courts of Alfred and Edward, and the Mercian dialect and scholarship commanded Westward Saxon respect.[53] It is uncertain how far Alfred's programmes continued during his son'southward reign. English language translations of works in Latin made during Alfred's reign continued to exist copied, just few original works are known. The script known every bit Anglo-Saxon Foursquare minuscule reached maturity in the 930s, and its earliest phases date to Edward's reign. The master scholarly and scriptorial centres were the cathedral centres of Canterbury, Winchester and Worcester; monasteries did non brand a significant contribution until Æthelstan's reign.[54] Very little survives of the manuscript production of Edward'southward reign.[55]

The only surviving large scale embroideries which were certainly made in Anglo-Saxon England date to Edward's reign. They are a stole, a maniple and a possible girdle removed from the bury of St Cuthbert in Durham Cathedral in the nineteenth century. They were donated to the shrine by Æthelstan in 934, only inscriptions on the embroideries show that they were commissioned by Edward'due south 2nd wife, Ælfflæd, as a souvenir to Frithestan, Bishop of Winchester. They probably did non reach their intended destination considering Æthelstan was on bad terms with Winchester.[56]

Law and administration [edit]

Nigh all surviving charters from Edward's reign are later copies, and the merely surviving original is not a charter of Edward himself, only a grant by Æthelred and Æthelflæd in 901.[57] In the aforementioned year a meeting at Southampton was attended past his blood brother and sons, his household thegns and nearly all bishops, merely no ealdormen. It was on this occasion that the king caused state from the Bishop of Winchester for the foundation of the New Minster, Winchester. No charters survive for the period from 910 to the rex'southward death in 924, much to the puzzlement and distress of historians. Charters were usually issued when the king fabricated grants of state, and it is possible that Edward followed a policy of retaining property which came into his hands to help finance his campaigns against the Vikings.[58] Charters rarely survive unless they concerned holding which passed to the church building and were preserved in their archives, and another possibility is that Edward was making grants of property only on terms which ensured that they returned to male members of the royal house; such charters would not be found in church archives.[59]

Clause 3 of the law code chosen I Edward provides that people convincingly charged with perjury shall not be allowed to clear themselves by oath, but simply past ordeal. This is the start of the continuous history in England of trial by ordeal; information technology is probably mentioned in the laws of Male monarch Ine (688 to 726),[c] merely not in afterwards codes such as those of Alfred.[lx] The administrative and legal system in Edward'due south reign may accept depended extensively on written records, near none of which survive.[61] Edward was 1 of the few Anglo-Saxon kings to issue laws about bookland. There was increasing confusion in the period every bit to what was really bookland; Edward urged prompt settlement in bookland and folkland disputes, and his legislation established that jurisdiction belonged to the king and his officers.[62]

Later life [edit]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in that location was a full general submission of rulers in U.k. to Edward in 920:

- Then [Edward] went from there into the Peak Commune to Bakewell and ordered a borough to be built in the neighbourhood and manned. And and so the king of the Scots and all the people of the Scots, and Rægnald and the sons of Eadwulf[d] and all who live in Northumbria, both English language and Danish, Norsemen and others, and also the king of the Strathclyde Welsh and all the Strathclyde Welsh, chose him every bit father and lord.[64]

This passage was regarded as a straightforward report by about historians until the late twentieth century,[65] and Frank Stenton observed that "each of the rulers named in this list had something definite to gain from an acknowledgement of Edward'southward overlordship".[66] Since the 1980s this submission has been viewed with increasing scepticism, peculiarly as the passage in the Relate is the only evidence for it, unlike other submissions such equally that 1 in 927 to Æthelstan, for which there is contained support from literary sources and coins.[67] Alfred P. Smyth points out that Edward was not in a position to impose the aforementioned weather on the Scots and the Northumbrians as he could on conquered Vikings, and argues that the Chronicle presented a treaty between kings as a submission to Wessex.[68] Stafford observes that the rulers had met at Bakewell on the border between Mercia and Northumbria, and that meetings on borders were more often than not considered to avert any implication of submission by either side.[69] Davidson points out that the wording "chosen every bit father and lord" applied to conquered regular army groups and burhs, not relations with other kings. In his view:

- The thought that this meeting represented a 'submission', while it must remain a possibility, does however seem unlikely. The textual context of the chronicler's passage makes his interpretation of the coming together suspect, and ultimately, Edward was in no position to strength the subordination of, or dictate terms to, his swain kings in U.k..[70]

Edward connected Æthelflæd's policy of founding burhs in the north-w, at Thelwall and Manchester in 919, and Cledematha (Rhuddlan) at the oral fissure of the River Clwyd in N Wales in 921.[71]

Zilch is known of his relations with the Mercians between 919 and the last twelvemonth of his life, when he put down a Mercian and Welsh revolt at Chester. Mercia and the eastern Danelaw were organised into shires at an unknown appointment in the tenth century, ignoring traditional boundaries, and historians such equally Sean Miller and David Griffiths suggest that Edward'due south imposition of direct control from 919 is a likely context for a alter which ignored Mercian sensibilities. Resentment at the changes, at the imposition of rule by afar Wessex, and at fiscal demands by Edward's reeves, may have provoked the defection at Chester. He died at the imperial estate of Farndon, twelve miles south of Chester, on 17 July 924, presently after putting down the revolt, and was buried in the New Minster, Winchester.[72] In 1109, the New Minster was moved outside the city walls to go Hyde Abbey, and the following yr the remains of Edward and his parents were translated to the new church.[73]

Reputation [edit]

Co-ordinate to William of Malmesbury, Edward was "much inferior to his male parent in the cultivation of letters", but "decidedly more than glorious in the power of his rule". Other medieval chroniclers expressed similar views, and he was more often than not seen as inferior in book learning, merely superior in military success. John of Worcester described him as "the almost invincible Male monarch Edward the Elder". Nevertheless, fifty-fifty as war leader he was only one of a succession of successful kings; his achievements were overshadowed because he did not take a famous victory like Alfred's at Edington and Æthelstan's at Brunanburh, and William of Malmesbury qualified his praise of Edward by saying that "the chief prize of victory, in my judgment, is due to his father".[e] Edward has also been overshadowed by chroniclers' admiration for his highly regarded sister, Æthelflæd.[74]

A principal reason for the neglect of Edward is that very few main sources for his reign survive, whereas there are many for Alfred. He was largely ignored by historians until the late twentieth century, simply he is now highly regarded. He is described by Keynes as "far more the bellicose scrap between Alfred and Æthelstan",[75] and according to Nick Higham: "Edward the Elder is perhaps the virtually neglected of English kings. He ruled an expanding realm for twenty-5 years and arguably did every bit much equally whatever other private to construct a single, s-centred, Anglo-Saxon kingdom, yet posthumously his achievements have been all just forgotten." In 1999 a conference on his reign was held at the Academy of Manchester, and the papers given on this occasion were published as a book in 2001. Prior to this conference, no monographs had been published on Edward's reign, whereas his male parent has been the subject of numerous biographies and other studies.[76]

In the view of F. T. Wainwright: "Without detracting from the achievements of Alfred, it is well to recollect that it was Edward who reconquered the Danish Midlands and gave England well-nigh a century of respite from serious Danish attacks."[77] Higham summarises Edward'southward legacy as follows:

- Under Edward's leadership, the calibration of culling centres of power diminished markedly: the dissever court of Mercia was dissolved; the Danish leaders were in large part brought to heel or expelled; the Welsh princes were constrained from aggression of the borders and even the West Saxon bishoprics divided. Late Anglo-Saxon England is often described equally the nearly centralised polity in western Europe at the time, with its shires, its shire-reeves and its systems of regional courts and royal taxation. If so — and the matter remains debatable — much of that axis derives from Edward's activities, and he has as good a claim as whatever other to be considered the builder of medieval England.[78]

Edward's cognomen 'the Elder' was first used in Wulfstan'southward Life of St Æthelwold at the end of the tenth century, to distinguish him from King Edward the Martyr.[xix]

Marriages and children [edit]

Edward had almost 14 children from three marriages.[f]

He commencement married Ecgwynn around 893.[84] Their children were:

- Æthelstan, Male monarch of England 924–939[19]

- A daughter, perhaps called Edith, married Sihtric, Viking King of York in 926, who died in 927. Mayhap Saint Edith of Polesworth[85]

In c. 900, Edward married Ælfflæd, daughter of Ealdorman Æthelhelm, probably of Wiltshire.[17] Their children were:

- Ælfweard, died Baronial 924, a calendar month later his father; mayhap Rex of Wessex for that calendar month[86]

- Edwin, drowned at ocean 933[87]

- Æthelhild, lay sister at Wilton Abbey[88]

- Eadgifu (died in or later 951), married Charles the Simple, Rex of the W Franks, c. 918[89]

- Eadflæd, nun at Wilton Abbey[88]

- Eadhild, married Hugh the Great, Knuckles of the Franks in 926[xc]

- Eadgyth (died 946), in 929/30 married Otto I, future King of the East Franks, and (after Eadgyth'southward death) Holy Roman Emperor[91]

- Ælfgifu or Edgiva, married "a prince virtually the Alps", peradventure Louis, blood brother of King Rudolph II of Burgundy[92]

Edward married for a third time, about 919, Eadgifu, the daughter of Sigehelm, Ealdorman of Kent.[93] Their children were:

- Edmund I, King of England 939–946[79]

- Eadred, King of England 946–955[79]

- Eadburh (died c. 952), Benedictine nun at Nunnaminster, Winchester, and saint[94]

- Eadgifu, being uncertain, possibly the same person as Ælfgifu[95]

Genealogy [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ The regnal numbering of English monarchs starts after the Norman conquest, which is why Edward the Elder, who was the first Rex Edward, is not referred to equally Edward I.

- ^ The twelfth-century chronicler Ralph of Diceto stated that the coronation took place at Kingston, and this is accustomed past Simon Keynes, although Sarah Human foot says that "Edward might well have held the ceremony at Winchester".[21]

- ^ It is not certain that the references in Ine's laws are to trial by ordeal.[lx]

- ^ Rægnald was the Norse Viking king of York in southern Northumbria, and Eadwulf was the Anglo-Saxon ruler of northern Northumbria, which was not conquered past the Vikings.[63]

- ^ All quotations in this paragraph are from Higham, 'Edward the Elder's Reputation: An Introduction', pp. 2-iii

- ^ The order in which Edward's children are listed is based on the family tree in Foot's Æthelstan: the First Rex of England, which shows sons of each wife before daughters. The daughters are listed in their nascence order co-ordinate to William of Malmesbury'due south Gesta Regum Anglorum.[79] The earliest chief sources do not distinguish whether Sihtric'southward wife was Æthelstan's full or half sister, and a tradition recorded at Bury in the early twelfth century makes her a daughter of Edward'due south second wife, Ælfflæd. She is described as the girl of Edward and Ecgwynn in William of Malmesbury'south 12th century Deeds of the English language Kings, and Michael Wood'due south argument that this is partly based on a lost early on life of Æthelstan has been generally accepted.[lxxx] Mod historians follow William of Malmesbury's testimony in showing her every bit Æthelstan'due south full sis."[81] William did not know her name, simply some tardily sources name her as Edith or Eadgyth, an identification accustomed by some historians.[82] She is also identified in tardily sources with saint Edith of Polesworth, a view accepted by Alan Thacker, merely dismissed as "dubious" past Sarah Pes, who thinks that it is likely that she entered the cloister in widowhood.[83]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Keynes and Lapidge 1983, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Stenton 1971, pp. 245–57.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 25–28.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 25–26; Miller 2004.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 25, 29–30.

- ^ Æthelhelm & PASE; Due south 356 & Sawyer; Yorke 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Keynes and Lapidge 1983, pp. 175–76, 321–22; Yorke 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 31–35.

- ^ Yorke 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Abels 1998, pp. 294–304.

- ^ Yorke 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Yorke 2001, pp. 33–34; Bailey 2001, p. 114; Mynors, Thomson and Winterbottom 1998, p. 199.

- ^ Keynes 1999, p. 467; Abels 1998, p. 307.

- ^ Yorke 2001, p. 33; Human foot 2011, p. 31.

- ^ a b Yorke 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Nelson 1996, pp. 53–54, 63–66.

- ^ a b c d e Miller 2004.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 321; Lavelle 2009, pp. 53, 61.

- ^ Keynes 2001, p. 48; Foot 2011, p. 74, n. 46.

- ^ Stenton 1971, pp. 321–322; Hart 1992, pp. 512–15; Miller 2004.

- ^ "Pseudo-coin; disc brooch; imitation". British Museum.

- ^ Keynes 2001, pp. 44–58.

- ^ a b Ryan 2013, p. 298.

- ^ Stafford 2001, p. 45.

- ^ Insley 2009, p. 330.

- ^ Davidson 2001, pp. 203–05; Keynes 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Sharp 2001, pp. 81–86.

- ^ Abrams 2001, p. 136.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 323; Heighway 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 324, n. 1; Wainwright 1975, pp. 308–09; Bailey 2001, p. 113.

- ^ Miller 2004; Stenton 1971, pp. 324–25.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 506; Miller 2004.

- ^ Stenton 1971, pp. 325–26.

- ^ Miller 2004; Stenton 1971, pp. 327–29.

- ^ Miller 2004; Stenton 1971, pp. 329–31.

- ^ Abrams 2001, pp. 138–39; Lyon 2001, p. 74.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 484, 498–500.

- ^ Lyon 2001, pp. 67–73, 77; Blackburn 2014.

- ^ Brooks 1984, pp. 210, 213.

- ^ Rumble 2001, pp. 230–31.

- ^ Yorke 2004b; Brooks 1984, pp. 212–13.

- ^ Rumble 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Rumble 2001, p. 231.

- ^ Thacker 2001, pp. 259–60.

- ^ Rumble 2001, pp. 231–34; Marafioti 2014, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Miller 2001, pp. xxv–xxix; Thacker 2001, pp. 253–54.

- ^ Rumble 2001, pp. 234–37, 244; Thacker 2001, p. 254.

- ^ Marafioti 2014, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Thacker 2001, p. 254.

- ^ Wormald 2001, pp. 274–75.

- ^ Gretsch 2001, p. 287.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 12–16.

- ^ Higham 2001a, p. two.

- ^ Coatsworth 2001, pp. 292–96; Wilson 1984, p. 154.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 13.

- ^ Keynes 2001, pp. 50–51, 55–56.

- ^ Wormald 2001, p. 275.

- ^ a b Campbell 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Campbell 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Wormald 2001, pp. 264, 276.

- ^ Davidson 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Davidson 2001, pp. 200–01.

- ^ Davidson 2001, p. 201.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 334.

- ^ Davidson 2001, pp. 206–07.

- ^ Smyth 1984, p. 199.

- ^ Stafford 1989, p. 33.

- ^ Davidson 2001, pp. 206, 209.

- ^ Griffiths 2001, p. 168.

- ^ Miller 2004; Griffiths 2001, pp. 167, 182–83.

- ^ Doubleday & Page 1903, pp. 116–22.

- ^ Higham 2001a, pp. 2–4; Keynes 2001, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Higham 2001a, pp. 3–9; Keynes 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Higham 2001a, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Wainwright 1975, p. 77.

- ^ Higham 2001b, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d Foot 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Thacker 2001, p. 257; Pes 2011, pp. 251–58.

- ^ Williams 1991, pp. xxix, 123; Pes 2011, p. xv; Miller 2004.

- ^ Miller 2004; Williams 1991, pp. xxix, 123.

- ^ Thacker 2001, pp. 257–58; Pes 2011, p. 48; Foot 2010, p. 243.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. eleven.

- ^ Thacker 2001, pp. 257–58.

- ^ Pes 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 21.

- ^ a b Human foot 2011, p. 45.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 46; Stafford 2011.

- ^ Human foot 2011, p. xviii.

- ^ Stafford 2011.

- ^ Human foot 2011, p. 51; MacLean 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Stafford 2004.

- ^ Yorke 2004a; Thacker 2001, pp. 259–threescore.

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 50–51; Stafford 2004.

Bibliography [edit]

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Bully: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Harlow, UK: Longman. ISBN978-0-582-04047-2.

- Abrams, Lesley (2001). "Edward the Elder's Danelaw". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 128–43. ISBN978-0-415-21497-i.

- "Æthelhelm 4 (Male)". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE). Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Bailey, Maggie (2001). "Ælfwynn, 2nd Lady of the Mercians". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Uk: Routledge. pp. 112–27. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Blackburn, One thousand. A. Due south. (2014). "Coinage". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2d ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley– Blackwell. pp. 114–fifteen. ISBN978-0-631-22492-1.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury. Leicester, U.k.: Leicester University Printing. ISBN978-0-7185-1182-1.

- Campbell, James (2001). "What is not Known About the Reign of Edward the Elderberry". In Higham, Nick; Loma, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 12–24. ISBN978-0-415-21497-one.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, Uk: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-xix-821731-two.

- Coatsworth, Elizabeth (2001). "The Embroideries from the Tomb of St Cuthbert". In Higham, Nick; Loma, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 292–306. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Davidson, Michael R. (2001). "The (Non)submission of the Northern Kings in 920". In Higham, Northward. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder, 899–924. Abingdon, Britain: Routledge. pp. 200–eleven. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Doubleday, Arthur; Page, William, eds. (1903). "New Minster, or the Abbey of Hyde". A History of the County of Hampshire. Victoria County History. Vol. 2. London, UK: Lawman. pp. 116–22. OCLC 832215096.

- Foot, Sarah (2010). "Dynastic Strategies: The West Saxon Imperial Family in Europe". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the 10th Century: Studies in Accolade of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 237–53. ISBN978-2-503-53208-0.

- Foot, Sarah (2011). Æthelstan: the First King of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Printing. ISBN978-0-300-12535-1.

- Gretsch, Mechtild (2001). "The Junius Psalter Gloss: Tradition and Innovation". In Higham, Nick; Loma, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, United kingdom: Routledge. pp. 280–91. ISBN978-0-415-21497-ane.

- Griffiths, David (2001). "The N-Due west Frontier". In Higham, Nick; Colina, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 167–87. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Hart, Cyril (1992). The Danelaw. London, UK: The Hambledon Printing. ISBN978-1-85285-044-nine.

- Heighway, Carolyn (2001). "Gloucester and the New Minster of St Oswald". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 102–11. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Higham, Nick (2001a). "Edward the Elderberry'due south Reputation: An Introduction". In Higham, Due north. J.; Loma, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elderberry, 899–924. Abingdon, U.k.: Routledge. pp. 1–11. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Higham, Nick (2001b). "Endpiece". In Higham, Due north. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elderberry, 899–924. Abingdon, Uk: Routledge. pp. 307–11. ISBN978-0-415-21497-i.

- Insley, Charles (2009). "Southumbria". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Uk and Ireland c.500- c.1100. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 322–40. ISBN978-i-118-42513-8.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). "England, c.900–1016". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. III. Cambridge, Great britain: Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–84. ISBN978-0-521-36447-8.

- Keynes, Simon (2001). "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder, 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. twoscore–66. ISBN978-0-415-21497-one.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources . London, United kingdom: Penguin Classics. ISBN978-0-fourteen-044409-four.

- Lapidge, Michael (1993). Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066 . London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN978-1-85285-012-eight.

- Lavelle, Ryan (2009). "The Politics of Rebellion: The Ætheling Æthelwold and the Westward Saxon Royal Succession, 899–902". In Skinner, Patricia (ed.). Challenging the Boundaries of Medieval History: The Legacy of Timothy Reuter. Turnhout, Kingdom of belgium: Brepols. pp. 51–80. ISBN978-two-503-52359-0.

- Lyon, Stewart (2001). "The coinage of Edward the Elderberry". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elderberry, 899–924. Abingdon, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Routledge. pp. 67–78. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- MacLean, Simon (2012). "Making a Difference in 10th-Century Politics: King Athelstan'south Sisters and Frankish Queenship". In Fouracre, Paul; Ganz, David (eds.). Frankland: The Franks and the Globe of the Early Middle Ages (Paperback ed.). Manchester, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Manchester University Press. pp. 167–ninety. ISBN978-0-7190-8772-1.

- Marafioti, Nicole (2014). The King'southward Body: Burial and Succession in Tardily Anglo-Saxon England. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Printing. ISBN978-1-4426-4758-9.

- Miller, Sean (2001). "Introduction: The History of the New Minster, Winchester". In Miller, Sean (ed.). Charters of the New Minster, Winchester. Oxford, Uk: Oxford University Press for The British Academy. pp. xxv–xxxvi. ISBN978-0-19-726223-8.

- Miller, Sean (2004). "Edward [called Edward the Elder] (870s?–924), male monarch of the Anglo-Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Academy Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8514. Retrieved 6 October 2016. (subscription or United kingdom public library membership required)

- Mynors, R. A. B.; Thomson, R.Thou; Winterbottom, 1000., eds. (1998). William of Malmesbury: The History of the English language Kings. Oxford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Clarendon Press. ISBN978-0-19-820678-1.

- Nelson, Janet (1996). "Reconstructing a Royal Family: Reflections on Alfred from Asser, Chapter 2". In Wood, Ian; Lund, Niels (eds.). People and places in Northern Europe 500-1600 : Essays in Accolade of Peter Hayes Sawyer. Woodbridge, Britain: Boydell Printing. pp. 48–66. ISBN978-0-851-15547-0.

- Rumble, Alexander R. (2001). "Edward and the Churches of Winchester and Wessex". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 230–47. ISBN978-0-415-21497-ane.

- Ryan, Martin J. (2013). "Conquest, Reform and the Making of England". In Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (eds.). The Anglo-Saxon Globe. New Oasis, Connecticut: Yale Academy Press. pp. 284–322. ISBN978-0-300-12534-iv.

- "South 356". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. Retrieved eighteen December 2017.

- Sharp, Sheila (2001). "The West Saxon Tradition of Dynastic Union, with Special Reference to the Family of Edward the Elder". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 79–88. ISBN978-0-415-21497-i.

- Smyth, Alfred P (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD fourscore–grand. London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Edward Arnold. ISBN978-0-7131-6305-6.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the 10th and Eleventh Centuries. London, Great britain: Edward Arnold. ISBN978-0-7131-6532-6.

- Stafford, Pauline (2001). "Political Women in Mercia, Eighth to Early Tenth Centuries". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol A. (eds.). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London, UK: Leicester University Press. pp. 35–49. ISBN978-0-7185-0231-7.

- Stafford, Pauline (2004). "Eadgifu (b. in or earlier 904, d. in or after 966), Queen of the Anglo-Saxons". Oxford Lexicon of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:ten.1093/ref:odnb/52307. Retrieved iv Jan 2017. (subscription or Britain public library membership required)

- Stafford, Pauline (2011). "Eadgyth (c.911–946), Queen of the E Franks". Oxford Lexicon of National Biography. Oxford University Printing. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93072. ISBN978-0-19-861411-ane . Retrieved iii January 2017. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (2001). "Dynastic Monasteries and Family unit Cults". In Higham, Nick; Colina, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 248–63. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Wainwright, F. T. (1975). Scandinavian England: Nerveless Papers. Chichester, UK: Phillimore. ISBN978-0-900592-65-2.

- Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (1991). A Biographical Lexicon of Dark Historic period U.k.: England, Scotland, and Wales. London, Uk: Seaby. ISBN978-1-85264-047-7.

- Wilson, David (1984). Anglo-Saxon Art from the Seventh Century to the Norman Conquest. London, UK: Thames and Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-23392-iv.

- Wormald, Patrick (2001). "Kingship and Purple Property from Æthelwulf to Edward the Elder". In Higham, Nick; Loma, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, Great britain: Routledge. pp. 264–79. ISBN978-0-415-21497-one.

- Yorke, Barbara (2001). "Edward as Ætheling". In Higham, Nick; Hill, David (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 25–39. ISBN978-0-415-21497-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (2004a). "Eadburh [St Eadburh, Eadburga] (921x4–951x3), Benedictine nun". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. Oxford University Printing. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49419. ISBN978-0-19-861412-8 . Retrieved 4 Jan 2017. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Yorke, Barbara (2004b). "Frithestan (d. 932/iii), bishop of Winchester". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:x.1093/ref:odnb/49428. Retrieved one March 2017. (subscription or United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland public library membership required)

External links [edit]

- Edward 2 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- The Laws of King Edward the Elderberry

- Edward the Elder Coinage Regulations

- Edward the Elder at Find a Grave

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_the_Elder

0 Response to "Read the Passage 1alfred I Ruled England"

Post a Comment