Correlates of Adults Participation in Physical Activity Review and Update

- Research commodity

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Correlates associated with participation in physical activity among adults: a systematic review of reviews and update

BMC Public Health volume 17, Article number:356 (2017) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

Agreement which factors influence participation in physical activity is important to improve the public wellness. The aim of the present review of reviews was to summarize and nowadays updated evidence on personal and environmental factors associated with physical activity.

Methods

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for reviews published up to 31 Jan. 2017 reporting on potential factors of physical activity in adults aged over 18 years. The quality of each review was appraised with the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist. The corrected covered expanse (CCA) was calculated as a measure out of overlap for the primary publications in each review.

Results

Twenty-five manufactures met the inclusion criteria which reviewed 90 personal and 27 environmental factors. The average quality of the studies was moderate, and the CCA ranged from 0 to 4.iii%. For personal factors, self-efficacy was shown as the strongest cistron for participation in concrete activity (7 out of 9). Intention to exercise, outcome expectation, perceived behavioral control and perceived fitness were positively associated with concrete activity in more than iii reviews, while age and bad status of wellness or fitness were negatively associated with participation in physical activity in more 3 reviews. For ecology factors, accessibility to facilities, presence of sidewalks, and aesthetics were positively associated with participation in concrete activity.

Conclusions

The findings of this review of reviews suggest that some personal and environmental factors were related with participation in physical action. Even so, an association of various factors with physical activeness could not be established because of the lack of primary studies to build up the organized show. More studies with a prospective design should be conducted to understand the potential causes for concrete activity.

Background

Participation in regular physical activity contributes to health promotion, improving concrete fitness, and prevention of non-catching diseases [i–iv]. The international health guideline for physical activity recommends that adults should exist doing at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week or doing at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity regardless of the domains of physical activity such equally leisure, transportation, occupational, and household chores [five]. However, the level of inactivity is reported to be high globally [half-dozen, vii]. Thus, motivating the public to participate in concrete activity by finding which factors influence participation in physical activity is important to improve the public health and to mitigate the global brunt of chronic diseases.

There are several theories that describe behavioral models of physical activeness, and information technology is common to incorporate ideas from these theories into ecological models. Co-ordinate to an ecological model, factors which influence health beliefs consisted of intra-personal, inter-personal, and environmental factors as well every bit policy [eight]. Personal factors include demographic and biological factors, psychological, cerebral and emotional factors, behavioral factors, and social and cultural factors [9]. Surround factors include the facility, neighborhood, safety, home environment, location of region, and climate [10].

Although in that location has been 1 meta-analysis of associations between environmental factors and physical action [xi], nigh factors related to physical activity have been summarized by systematic reviews rather than by meta-analysis because of an bereft number of main studies on each factor and distinct analytical methods. In a report by Bauman, the authors conducted a review of reviews which is a capable method of summarizing previous evidence from systematic reviews, with or without synthesis [12, thirteen]. They reviewed variables as determinants of concrete activity in children or boyish among adults to investigate those factors throughout their life span; however, the variables studied in adults, but not in children or adolescents, were not reviewed [14].

The chief purpose of this report was to summarize and nowadays updated bear witness for personal and ecology factors potentially associated with participation in concrete activity overall or past the domains of concrete activeness.

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

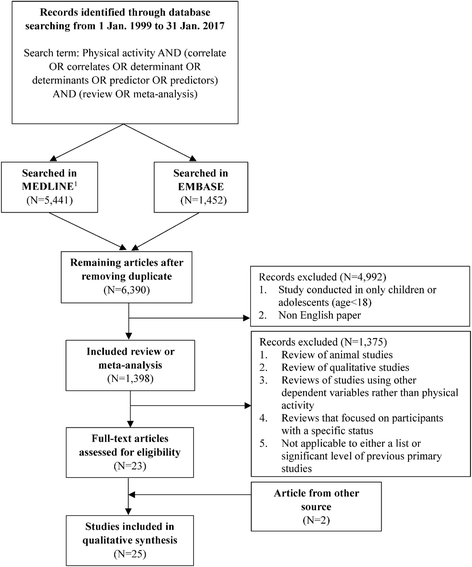

To place systematic reviews, MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for quantitative, peer-reviewed studies published up to 31 Jan. 2017 reporting on potential correlates, predictors or determinants of any type of physical activity in adults aged over eighteen years (Fig. 1). Search terms indicative of physical activity were used in combination with correlates or determinants. For the adaption of search strategies, specific filters were used from the databases including study design, publication year, linguistic communication, and historic period. In MEDLINE, medical field of study headings (MeSH) such as 'motor activity' and 'epidemiologic factors' were also used in the search strategy.

Catamenia nautical chart of inclusion and exclusion criteria for previous reviews. 1Medical subject headings (MeSH) such every bit 'Motor Activity' and 'Epidemiologic Factors' were besides used in the search strategy

Afterward the removal of reviews that were duplicates in both literature databases or published in a non-English language language or that targeted adolescents, the additional following reviews were excluded: 1) reviews of animal studies, 2) reviews of qualitative studies, iii) reviews of studies using other dependent variables rather than physical action, iv) reviews that focused on participants with a specific status such every bit cancer, pregnancy, and booze utilise disorder, and 5) studies which did not provide either a list or pregnant level of previous primary studies because that data was used in the classification of the variables. Reference lists of the included reviews and chief studies in each review were checked to identify whatsoever unrevealed studies.

Rating the methodological quality

To assess the quality of each included review, the 11-item Assessment of Multiple Systematic Review (AMSTAR) checklist was used for the assessment [15]. The measure satisfies inter-observer agreement, reliability, construct validity and feasibility. The quality score ranges from 0 (lowest quality) to xi (highest quality). In the current study, a review with a 0–two AMSTAR score was considered equally having a low quality, 3–6 every bit having a moderate quality and 7–eleven as having a high quality. The checklist of the AMSTAR score is provided in Boosted file 1: Table S1.

Information extraction

The post-obit characteristics were extracted from the included reviews: report type (e.one thousand., systematic review or meta-assay), publication yr, age of population, number of quantitative studies, outcomes, and proportion of longitudinal studies, and measurement method of physical activity and environmental factors. The domains of physical activeness were collected as the outcome if the results of the principal studies included in each review were identifiable past the domains of physical activity.

Classification of variables

Variables from each review were classified according to the number of principal studies supporting the association or no clan and the pct of expected clan amidst the full number of primary studies (Additional file 1: Table S2) [xiv]: not a correlate (NC) or not a determinant (ND), inconclusive (IC), a correlate (Cor) or determinant (Det). When more than 50% of the primary studies supporting an association or no association were derived from a longitudinal design, the variables were coded every bit a determinant rather than a correlate. If the factors were classified equally a 'correlate' or a 'determinant', information technology was regarded as a definitely associated factor (DAF).

Corrected Covered Surface area (CCA)

Because some primary studies were included in more than one review, the summarized results from each review can exist biased past those overlaps. To assess this bias, the degree of overlap between reviews was calculated with the Corrected Covered Area (CCA) method. The details of the CCA calculation have been described elsewhere [16]. Briefly, the CCA was calculated with the following equation showing how the primary studies in each review are duplicated:

$$ \mathrm{Corrected}\ \mathrm{Covered}\ \mathrm{Surface area}\kern0.5em \left(\mathrm{CCA}\right)=\frac{Due north- r}{rc- r} $$

where Northward is the sum of the number of primary studies in each review, r is the total number of primary studies, and c is the number of reviews. This measure has been validated in which the number of overlapped chief publications has a strong correlation with the CCA. A CCA score of less than 5% is regarded as a slight overlap, 5–9.ix% equally moderate overlap, 10–14.9% as loftier overlap and over fifteen% as a very loftier level of overlap [16]. The CCA was estimated for overall personal and ecology factors as well every bit for the factors classified as DAFs in more than 3 reviews. A report by Duncan et al. [eleven] was excluded in the CCA adding because the list of included main studies was not available.

Results

A total of 25 reviews with 980 primary studies met the inclusion criteria [nine–11, 17–38]. Amongst those reviews, at that place were 13 reviews with personal factors [ix, 10, 17, 19, 22, 23, 26, 28, 32–34, 36, 38] and 19 reviews with environmental factors [9–11, 18–21, 24, 25, 27–31, 33, 35–38], respectively (Table 1). The number of master studies for personal factors included in each review ranged from eleven to 91, and the number of primary studies for environmental factors ranged from three to 70. Iv reviews included only primary studies conducted with a longitudinal pattern [28, 33, 36, 38]. Thus, the results derived from those reviews were regarded as a determinant rather than equally a correlate. Reviews published before 1999 were not considered in the nowadays written report because a written report by Trost et al. [nine] had included and updated the results of those reviews [39–42].

The quality cess scores are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1. The AMSTAR score for each review ranged from 2 to 8. Most of the reviews (21 out of 25) were rated as having a moderate quality. Information on written report blueprint (checklist 1), literature search strategy (checklist three) and list of included studies (checklist 5) were provided in nigh studies. However, information on the condition of the publication as an inclusion criterion (checklist iv), the combining methods (checklist 9), publication bias assessment (checklist ten) and disharmonize of interest of the included studies (checklist 11) were rarely provided.

Correlates of physical activity overall

A total of 117 factors were reported in the previous reviews. The definitions of each gene are shown in Boosted file 1: Table S3 in alphabetical order.

Table 2 lists the relationships between personal factors and physical activity overall. There were 90 personal factors consisting of 24 demographic/biological factors, forty psychological factors, xiii behavioral factors, and 13 social factors. Amid the 90 personal factors, 53 factors were considered as DAFs in more than one of the reviews. For demographic and biological factors, age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and employment were assessed in more half of the reviews (seven out of 13). Amongst those, historic period was regarded equally a negative DAF in 3 reviews. Bad wellness or fettle status was assessed in 5 reviews and classified as a negative DAF in iii reviews. For psychological factors, cognitive and emotional factors, attitude, intention to exercise, outcome expectations, cocky-efficacy, and stress were assessed in more than half of the reviews. Intention to do, effect expectations, perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy and perceived practiced fettle were assessed as positive DAFs in more than 3 reviews. Self-efficacy classified as a DAF in vii reviews had the strongest clan with participation in physical activity in this review of reviews. For behavioral factors, smoking was assessed in 7 reviews, which was not determined every bit a DAF in whatever of the reviews. For social and cultural factors, there were no variables evaluated in more than half of the reviews.

Table 3 lists the relationships betwixt environmental factors and physical activity overall. In that location were 27 environment factors consisting of 4 facility factors, 8 neighborhood factors, half-dozen safety factors, 3 domicile environment factors, iii location of region factors, and three climate factors. Among the 27 environmental factors, x factors were considered as DAFs in more than than i of the reviews. For facility factors, accessibility was assessed in more half of the reviews (ten out of 19) and classified as a positive DAF in 5 reviews. For neighborhood factors, the presence of sidewalks and aesthetics were evaluated in 14 reviews and regarded equally positive DAFs in more three reviews. For safety factors, high criminal offense rates in the region and heavy traffic were only determined every bit DAFs in less than three reviews although they were summarized in more than half of the reviews. There were no factors which were assessed in more than than one-half of the reviews (ten out of 19) for home surroundings, location of region, and climate factors.

Correlates of physical action past the domains of the physical activity

The results by the domains of concrete activity are summarized in Additional file 1: Tables S4 ~ S7. For personal factors, the factors for leisure-time concrete activeness were summarized (Additional file 1: Table S4). Of the 46 personal factors, twenty-two factors were considered as DAFs in i of the reviews. There were no personal factors considered more twice as a DAF. For environmental factors, factors were summarized in leisure time concrete activity, walking/cycling, and transportation, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S5 ~ S7). There were 6 factors regarded equally DAFs in more than than one of the reviews. Accessibility was considered as a DAF in all three domains. Population density and high crime rate in the region were considered as DAFs simply in the leisure-time physical activity domain (Boosted file 1: Table S5). State-use mix and urban location were classified every bit DAFs in transportation (Additional file 1: Table S6) and walking/cycling (Additional file i: Table S7). Aesthetics was considered in one case equally a DAF only in the walking/cycling domain (Additional file 1: Table S7). The results for the occupation and household domain could be not summarized for both personal and environmental factors considering in that location was just ane or no reviews for those domains.

Other issues for correlates of physical activeness

When summarizing the review of studies conducted in older subjects, no differences were found when compared with the results for all adults. In that location were 13 personal factors which were classified as DAFs in at least one of ii reviews that only focused on factors of older adults (> 65 years) (Come across the results of Rhode et al. [17] and Plonczynski et al. [19] in Table ii). There were no ecology factors considered as DAFs for older adults.

The results of objectively measured physical activeness could be not summarized in this review of reviews considering well-nigh of the reviews included less than four chief studies using objectively measured physical activeness or did not provide information on the measurement of physical activity in the primary studies. In the results of objectively measured environmental factors, the following five factors were considered equally DAFs in more than 1 of the reviews from amongst 17 factors: accessibility, population density, state-use mix, urban location, and high crime charge per unit in the region (Additional file ane: Tabular array S8).

Corrected Covered Expanse (CCA)

Additional file 1: Table S9 presents the CCA for each gene. The master studies had a slight overlap across 13 (CCA: 2.0%) and 18 reviews (CCA: 1.vi%) for personal and environmental factors, respectively. In add-on, all the CCAs for the factors classified as DAFs in more than 3 reviews were less than 5%.

Discussion

This review of reviews summarized the results of 25 previous reviews that reported on the potential factors of participation in concrete activity all of which showed more often than not a moderate methodological quality. Several personal factors including age, health or fitness status, intention to do, event expectations, perceived behavioral control, cocky-efficacy, and perceived fitness and several environmental factors including accessibility, presence of sidewalks, and aesthetics were assessed equally DAFs in more than three studies.

This study is the first updated review of reviews on factors for physical activity after the study past Bauman in 2012 [13]. 4 reviews for personal factors [10, 34, 36, 38] and ten reviews for ecology factors [nine, 10, 19, 24, thirty, 33, 35–38] were added in the present study subsequently the previous review of reviews [13]. Most factors presented equally correlates in the study by Bauman were considered equally DAFs in the present study including personal history of physical action during adulthood which was classified as a DAF in two reviews. 50-four factors were additionally summarized which were not evaluated in the review by Bauman. Amongst them, transition to university, pregnancy, past do program, processes of behavioral change, change in family structure, presence of sidewalks, and flavor were classified as DAFs at least one time. A summary of previous reviews by the domains of physical action and past measures of environmental factors was added.

For personal factors, cocky-efficacy was consistently evaluated as the clearest correlate in the present study consistent with the previous review of reviews [13]. Co-ordinate to Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy functions both directly and indirectly with consequence expectations and other constructs [43] and has a role as a mediating cistron of social support in health behavior [44, 45].

For environmental factors, this study summarized the factors past the domains of physical activity, and the results of some factors such equally accessibility were consequent overall and by the domains of physical activity. However, it can be concluded that it is likewise early to summarize the results of the review because at that place were a limited number of chief studies for each factor.

Although there were a number of factors whose effects on physical activeness were assessed, we could non perform a meta-analysis considering of the lack of primary studies for each factor, dissimilar belittling measures, and the presence of unclearly distinguished factors when compared with each other. For case, some psychological factors had like definitions such every bit attitude and consequence expectation. There were many factors classified as a group such as employment-related factors including occupation type, employment status, total work hours, overtime piece of work hour, fixed day time work, shift work, multiple task, and full fourth dimension employment and social support-related factors including social back up for practise overall and from friends/peers, spouse/family, and staff/instructor and those factors were listed in their originally written form from each review to convey the about accurate significant of each cistron rather than conducting a meta-analysis.

Instead of a meta-analysis, the present report conducted a review of reviews. Although a review of reviews can only show the tendency or direction of an association rather than providing the magnitude or significance level of an clan [46], the current evidence on participation in physical activity was comprehensively summarized. When using the review of reviews, in that location were some challenges. First, the quality of the review of reviews was greatly affected by the quality of the original reviews [47]. In this study, nosotros confirmed that the quality of the original reviews were mostly moderate or higher by assessing the AMSTAR score. Second, if the master studies were included in several reviews, they may produce bias related to overlapping effects [47]. Past computing the CCA, we showed that the chief studies included in each review were only slightly overlapped and proved that the results from each review were relatively contained.

The present written report has limitations. First, a study past Duncan [11] was not included in the adding of the CCA considering it did not provide a list of the included primary studies. Yet, the event of non including these primary studies is expected to be slight because there were only 16 primary studies in the study by Duncan. Second, the results of intervention and observational studies could not exist separately summarized because the results were not presented separately for each design in most reviews. Farther studies should summarize the effects of potential factors on concrete activeness by the design of the study. Third, policy-related variables were not considered in the present study because policies were rarely considered in previous reviews. Although the effects of policy-related factors were overlapped with the effects of ecology factors such as the presence of sidewalks, the effects of policies on participation in physical action should be investigated in a time to come report. Fourth, the interaction effect betwixt different types of factors such as historic period and presence of sidewalks could non be assessed because the previous reviews were only focused on the individual outcome of each factor. Like the interaction effect, the moderating effect of individual factors such as gender and historic period could non be evaluated also because at that place were no reviews on this result. Future enquiry should exist conducted to place the interaction or moderating result of each factor.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study summarized the associations of potential factors with physical activity which could provide directions for improving participation in concrete activeness. More studies with a longitudinal design are needed to validate the associations of many factors. If more correlates are established with an accurate method, those factors can exist used to grade public policies and programs that will encourage the public to participate in physical action and ultimately better the public health.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews

- CCA:

-

corrected covered area

- Cor:

-

correlate

- DAF:

-

definitely associated factor

- Det:

-

determinant

- IC:

-

inconclusive

- MeSH:

-

medical subject heading

- NC:

-

not correlate

- ND:

-

not determinant

References

-

Berlin JA, Colditz GA. A meta-analysis of concrete activity in the prevention of coronary center disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(4):612–28.

-

Thune I, Brenn T, Lund Eastward, Gaard M. Physical activity and the adventure of chest cancer. North Engl J Med. 1997;336(xviii):1269–75.

-

Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Fuchs CS. Physical action, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2001;286(eight):921–9.

-

Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activeness: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006, 174(half dozen):801–809.

-

Arrangement WH: Global recommendations on physical activeness for health. 2010.

-

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Upshot of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an assay of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet (London, England). 2012, 380(9838):219–229.

-

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global concrete activeness levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet (London, England). 2012, 380(9838):247–257.

-

Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health beliefs. Health Behav: Theory Res practice. 2015;v:43–64.

-

Trost SG, Owen North, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brownish W. Correlates of adults' participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001.

-

Eyler AE, Wilcox Due south, Matson-Koffman D, Evenson KR, Sanderson B, Thompson J, Wilbur J, Rohm-Young D. Correlates of concrete activity among women from various racial/ethnic groups. J Women's Health Gender-Based Med. 2002;11(iii):239–53.

-

Duncan MJ, Spence JC, Mummery WK. Perceived environment and physical action: a meta-assay of selected environmental characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2

-

Baker PR, Costello JT, Dobbins M, Waters EB. The benefits and challenges of conducting an overview of systematic reviews in public health: a focus on concrete action. J Public Health. 2014;36(three):517–21.

-

Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically agile and others not? Lancet (London, England). 2012, 380(9838):258–271.

-

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activeness of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–75.

-

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers Chiliad, Andersson Due north, Hamel C, Porter Air-conditioning, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Evolution of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

-

Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, Neugebauer EA, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were non mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):368–75.

-

Rhodes RE, Martin AD, Taunton JE, Rhodes EC, Donnelly Yard, Elliot J. Factors associated with practice adherence among older adults. An individual perspective. Sports Med. 1999;28(6):397–411.

-

Humpel N, Owen Northward, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults' participation in physical activity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(3):188–99.

-

Plonczynski DJ. Physical activeness determinants of older women: what influences activeness? Medsurg Nurs. 2003;12(four):213–21. 259; quiz 222

-

Cunningham Become, Michael YL. Concepts guiding the study of the impact of the built environment on physical activity for older adults: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot. 2004;eighteen(6):435–43.

-

Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking: review and research calendar. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):67–76.

-

Kaewthummanukul T, Brown KC. Determinants of employee participation in physical activity: disquisitional review of the literature. AAOHN J. 2006;54(6):249–61.

-

Rhodes RE, Smith NEI. Personality correlates of physical activeness: a review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(12):958–65.

-

Tucker P, Gilliland J. The effect of season and weather condition on physical activity: a systematic review. Public Health. 2007;121(12):909–22.

-

Wendel-Vos Due west, Droomers Yard, Kremers S, Brug J, van Lenthe F. Potential environmental determinants of physical activeness in adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(5):425–40.

-

Allender S, Hutchinson L, Foster C. Life-modify events and participation in concrete action: a systematic review. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(ii):160–72.

-

Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S550–66.

-

van Stralen MM, De Vries H, Mudde AN, Bolman C, Lechner L. Determinants of initiation and maintenance of concrete activity among older adults: a literature review. Health Psychol Rev. 2009;3(2):147–207.

-

Panter JR, Jones A. Attitudes and the environment as determinants of active travel in adults: what do and don't we know? J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(4):551–61.

-

McCormack GR, Shiell A. In search of causality: a systematic review of the relationship betwixt the built environment and concrete activity among adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Deed. 2011;xiii(8):125.

-

Van Cauwenberg J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Meester F, Van Dyck D, Salmon J, Clarys P, Deforche B. Relationship betwixt the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Health Place. 2011;17(2):458–69.

-

Kirk MA, Rhodes RE. Occupation correlates of adults' participation in leisure-fourth dimension physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(iv):476–85.

-

Koeneman MA, Verheijden MW, Chinapaw MJM, Hopman-Rock M: Determinants of physical activeness and exercise in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;28(eight):142.

-

Engberg East, Alen M, Kukkonen-Harjula Yard, Peltonen JE, Tikkanen HO, Pekkarinen H. Life events and change in leisure fourth dimension physical activity: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2012, 42(5):433–447.

-

Van Holle V, Deforche B, Van Cauwenberg J, Goubert L, Maes L, Van de Weghe Northward, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Relationship between the physical surround and different domains of physical activity in European adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):807.

-

Rhodes RE, Quinlan A. Predictors of physical action modify amid adults using observational designs. Sports Med. 2015, 45(three):423–441.

-

Day G. Congenital environmental correlates of physical activity in Cathay: a review. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:303–16.

-

Prince SA, Reed JL, Martinello N, Adamo KB, Fodor JG, Hiremath S, Kristjansson EA, Mullen KA, Nerenberg KA, Tulloch HE, et al. Why are adult women physically agile? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies to identify intrapersonal, social environmental and physical environmental determinants. Obes Rev. 2016;17(x):919–44.

-

Dishman RK, Sallis JF, Orenstein DR. The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):158.

-

Dishman RK, Chubb M, Bouchard C, Shephard R, Stephens T, Sutton J, McPherson B. Determinants of participation in physical activity. In: Exercise, fitness, and wellness: a consensus of electric current knowledge: proceedings of the International Conference on Exercise, fettle and health, May 29–June iii, 1988. Toronto, Canada: Human Kinetics Publishers; 1990: 75–108.

-

Dishman RK. Advances in exercise adherence: human being kinetics publishers; 1994.

-

Sallis JF, Owen N. Physical activeness and behavioral medicine, vol. 3. Thousand Oaks: SAGE publications; 1998.

-

Bandura A: Social foundations of thought and activity: a social cognitive theory: prentice-hall, inc; 1986.

-

Duncan TE, McAuley E. Social support and efficacy cognitions in exercise adherence: a latent growth bend assay. J Behav Med. 1993;sixteen(2):199–218.

-

McNeill LH, Wyrwich KW, Brownson RC, Clark EM, Kreuter MW. Individual, social environmental, and physical environmental influences on physical activity amongst black and white adults: a structural equation analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(ane):36–44.

-

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15.

-

Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Fernandes RM. Systematic reviews, overviews of reviews and comparative effectiveness reviews: a discussion of approaches to knowledge synthesis. Evid Based Child Wellness. 2014;9(ii):486–94.

Acknowledgement

This report was supported by a grant from Seoul National Academy Hospital (2016) and Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004-E71004-00, 2005-E71011-00, 2005-E71009-00, 2006-E71001-00, 2006-E71004-00, 2006-E71010-00, 2006-E71003-00, 2007-E71004-00, 2007-E71006-00, 2008-E71006-00, 2008-E71008-00, 2009-E71009-00, 2010-E71006-00, 2011-E71006-00, 2012-E71001-00, and 2013-E71009-00).

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Seoul National Academy Hospital (2016) and Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004-E71004–00, 2005-E71011–00, 2005-E71009–00, 2006-E71001–00, 2006-E71004–00, 2006-E71010–00, 2006-E71003–00, 2007-E71004–00, 2007-E71006–00, 2008-E71006–00, 2008-E71008–00, 2009-E71009–00, 2010-E71006–00, 2011-E71006–00, 2012-E71001–00, and 2013-E71009–00).

Authors' contributions

JC conducted the literature searches, the choice of reviews, the data extraction, the quality rating and the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. ML, JKL and DK were involved in the study as advisors and were as well involved in commenting on the manuscript. JYC conducted the literature searches, the selection of reviews, the information extraction, the quality rating and the data assay, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding draft.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

AMSTAR score for each review. Table S2. Modified classification of the variables from each review based the testify from the primary studies. Table S3. Definition of each cistron. Table S4. Relationships between personal factors and leisure-time physical activity. Table S5. Relationships between environmental factors and leisure-time concrete activity. Table S6. Relationships between environmental factors and transportation. Table S7. Relationships between environmental factors and walking/cycling. Table S8. Relationships between objectively measured environmental factors and physical activity. Table S9. CCA for each factor. (DOCX 85 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Choi, J., Lee, M., Lee, Jk. et al. Correlates associated with participation in concrete activity amidst adults: a systematic review of reviews and update. BMC Public Health 17, 356 (2017). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12889-017-4255-ii

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4255-two

Keywords

- Concrete activity

- Epidemiologic factors

- Review of reviews

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4255-2

0 Response to "Correlates of Adults Participation in Physical Activity Review and Update"

Post a Comment